The Swimmin's Not Fine

on public pools and public schools

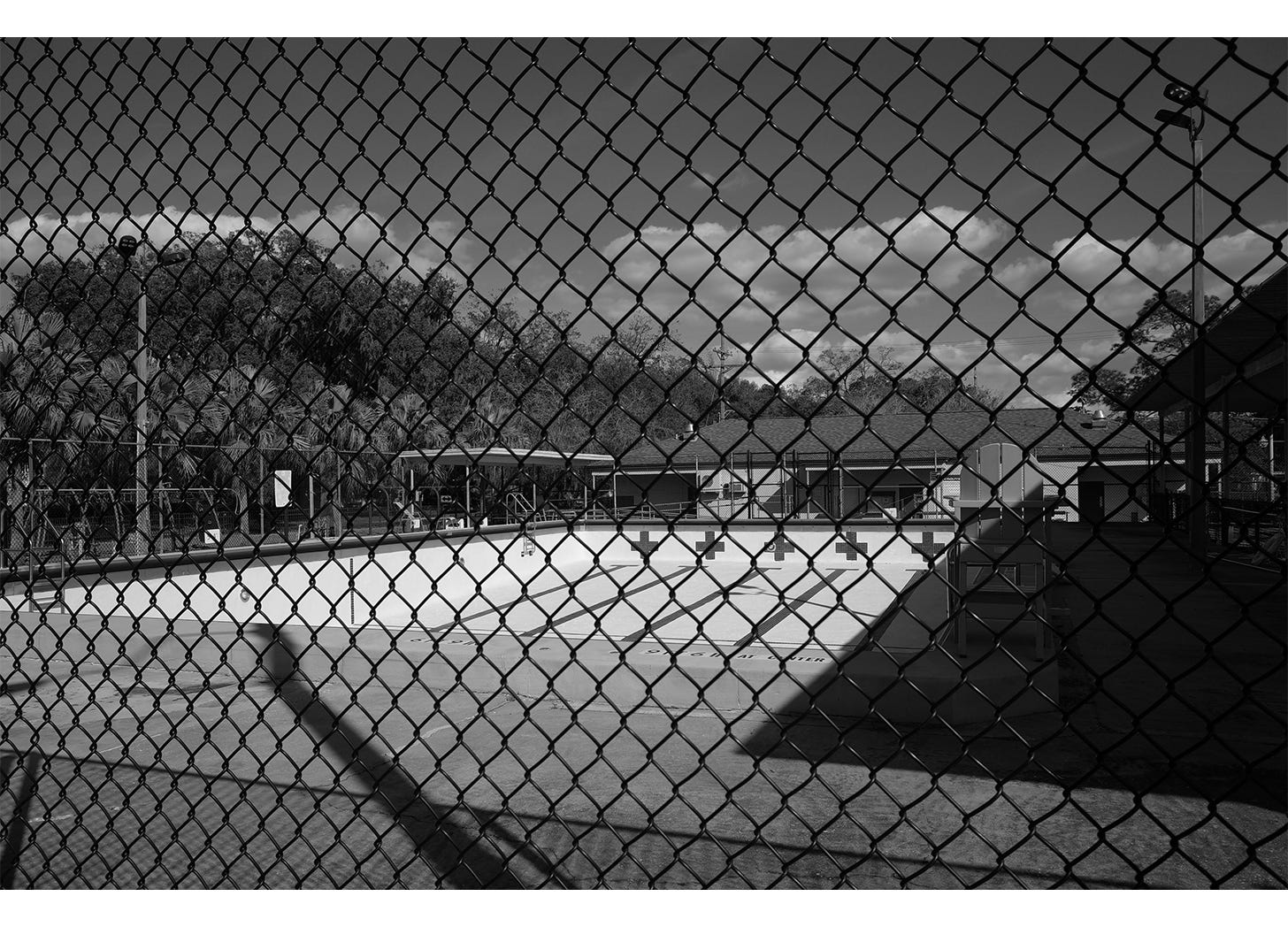

During one of many pandemic walks, I took a photo of the John Long Memorial Pool at the Colonialtown Neighborhood Center. It’s not visible from the street, but the marquee on the side of the building announced the pool was “closed for safety and renovations,” so I walked around the back and snapped some shots using an actual camera (not my trusty phone) borrowed from my good buddy Jared Silvia. By chance, I’d been shooting in black and white all day.

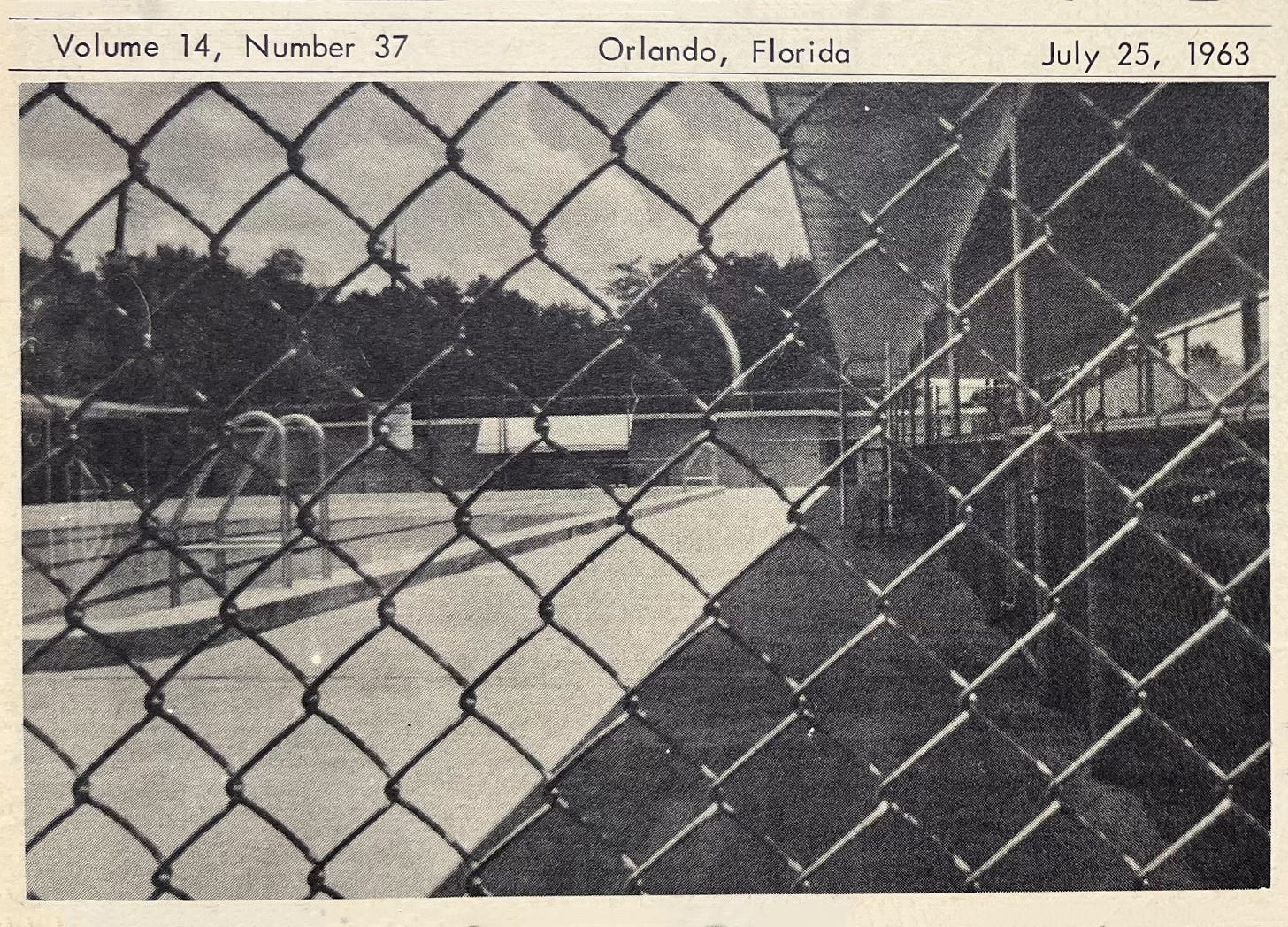

The Colonialtown Neighborhood Center was once a white-only women’s club before it became a segregated community center. The emptiness of the pool on that day, drained due to Covid-19, evoked the era when white-run municipalities nationwide drained public pools to avoid integration. In reaction to peaceful protests, Orlando closed public lakes as well, claiming high bacteria counts endangered swimmers. In the summer of 1963, young Black activists staged a wade-in at the John Long Pool, after which the city shut the facility down indefinitely.1 I’d read about this protest in The Florida Historical Quarterly and tracked the source to a now defunct local paper called The Corner Cupboard.

Just last year, I was able to browse the Cupboard archives at the Orange County Regional History Center. Each year’s worth of issues was leather bound and kept in a rectangular box. As I browsed the issues from early 1963 leading up to July, I was struck by the numerous ads for private pools. “Pools often pay for themselves in money saved on vacations and summer camp for the children,” one ad boasted. On the cover of the issue right before the article about the wade-in, a white woman is climbing out of the pool at the Cherry Plaza Hotel, “where she and 10-year-old Carol Lynn are frequent visitors these warm summer days.” Directly below the image is a headline about the ongoing struggle for integration in Orlando.

When I finally arrived at the issue about the wade-in, I was struck by an another striking juxtaposition: the cover photo of the John Long Pool in 1963 looked eerily similar to the photo I’d taken in 2020.

This overlaying of time periods is a trademark of the gothic. In gothic literature, the trope of disjointed time often represents the past haunting the present. The uncanny echo between these photos only resonates because our present is still haunted by systemic racism.

When the second photo was taken, about a mile down the road from the site of the wade-in, protestors in downtown Orlando were once again marching against a morbid cycle of racist police violence. The amnesiac news networks called 2020 a “racial reckoning,” as if they had not also said this about 2014. . . 2012 . . . 1999 . . . 1955 . . . A white nationalist TV personality claimed liberals wanted to “abolish the suburbs.” The president warned they would “abolish single-family homes.” These oddly specific dogwhistles harkened back to the era of the public pool closings and the broader retreat of suburban whiteness away from public space in the face of integration.

In the wake of the 1954 Brown v. Board decision, the prospect of school integration looming, the US congress, led by Southern states, held a series of hearings on the potential effects of the ruling, which amounted to blatantly racist attacks that maligned Black youth as inherently unintelligent, criminal, hypersexual, and, maybe most whitely, suggested these traits were somehow physically contagious and risked contaminating white children. This moral panic in part contributed to white flight and the creation of the suburbs.2

In Florida, where racial segregation was enshrined in the state’s 1885 constitution, the Brown decision was considered an “emergency” and a “crisis,” though officials state-wide urged “calm” and “sanity,” for citizens to meet the news with “mature emotional attitudes.” The Superintendent of the Florida Continuing Educational Council called for “planning untainted by hysteria.”3

This rhetoric, however, contradicted the relentless legal and political obstruction that followed. “Between 1954 and 1959 the Florida legislature approved twenty-one laws designed to keep public schools segregated.”4 Defiant of even Plessy v. Ferguson, the state’s separate schools had always been unequal, but in a sad attempt to delay the inevitable, white bureaucrats proposed the improvement of Black schools as an alternative to integration. Policy was also reinforced by white terror, including the 1958 bombing of James Weldon Johnson Middle School in Jacksonville.5

Physical violence aside, the political ideas for undermining Brown were the epitome of hysterical: a 1959 Constitutional Advisory Committee not only recommended keeping Florida’s original provision for segregation, it also (no doubt quite calmly) suggested “an amendment to our State Constitution which would permit the abolition of the system of free public schools.”6 This is the same zero-sum mentality reflected in the closing of public pools. The masochistic “logic” of whiteness would prefer no public goods to sharing anything with nonwhite people. This strand of thinking played a part in how the word “private” was (and is still) code for “white.”

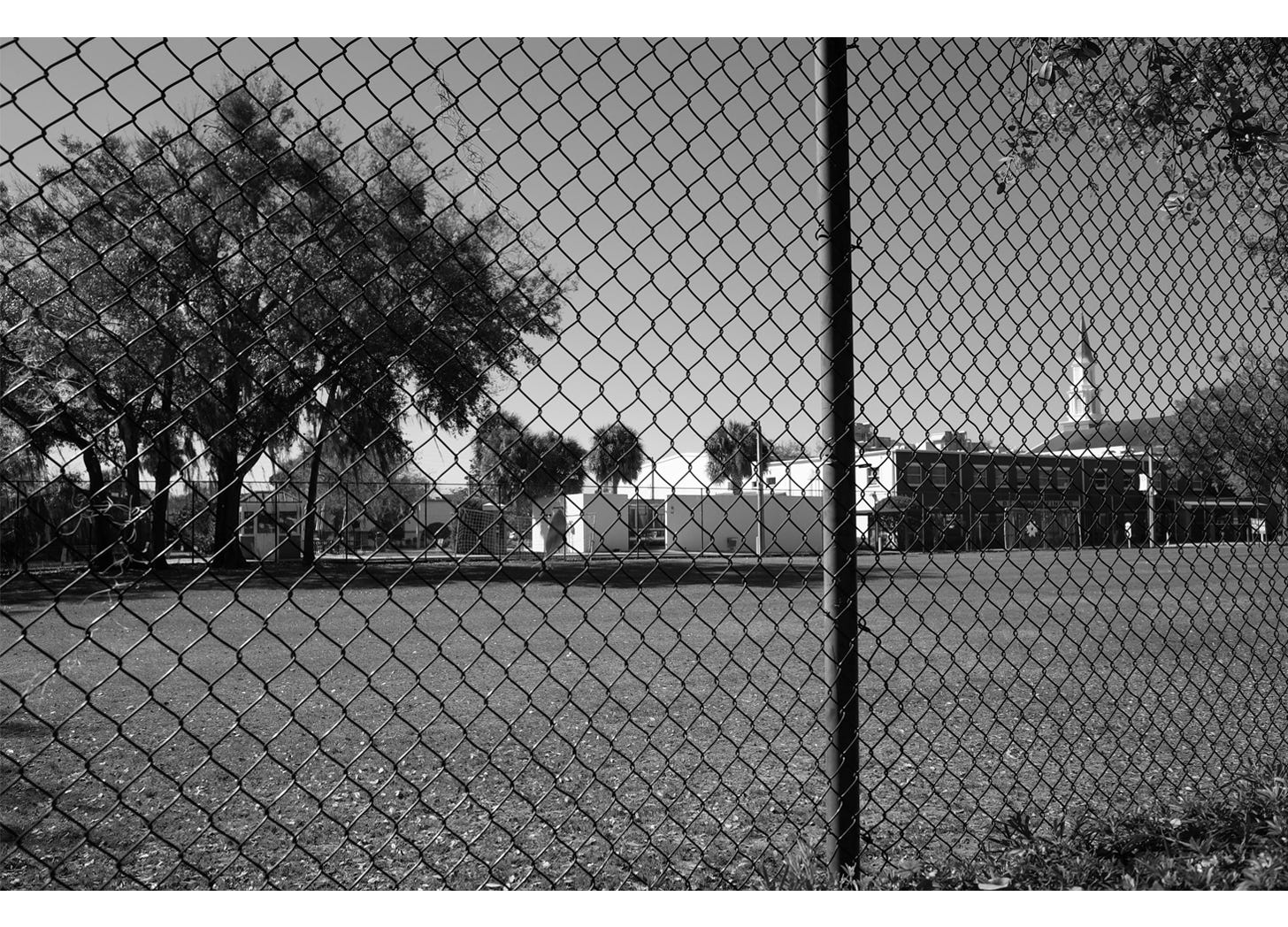

Amid the scramble to avoid integration, private white Christian schools known as “segregation academies” formed nationwide, including Lake Highland Preparatory School, now ostensibly integrated and “nestled in a scenic enclave of downtown Orlando”7 called Colonialtown North. In lieu of imploding the Florida school system, the legal battles continued into the very recent past. Orange County Public Schools, for instance, did not achieve “unitary status” until 2010, meaning it was only 15 years ago that the district “implemented its school desegregation order in good faith, and eliminated past vestiges of school segregation.”8

And yet, as of 2020, the average white student in Orlando attended schools with disproportionately smaller shares of nonwhite students than exist in the County (about 64%).9 The racist stereotypes about Black youth continue to manifest in schools via disproportionate punishments: in Orange County, “black students made up 27.5 percent of the population and 51 percent of those suspended.”10

In the face of facts and statistics we continue to see an attack on education, particularly Black History, in the form of the Florida Governor’s moral panic over “woke” and “critical race theory” – the stupidity of which is not worth rehashing. What is noteworthy to me is the repetition, the historical echo. How many times must we be confronted by racism before we actually have a “racial reckoning”?

Repression, historical amnesia, willful denial. The inability or refusal to see the connection between then and now. These are features, not bugs, of whiteness, and this mode of being creates the conditions for the gothic to thrive.

“Segregation and Desegregation in Parramore: Orlando's African American Community,” Tana Mosier Porter, The Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 82 No. 3, Winter 2004.

“Scared in the Suburbs,” United States of Anxiety podcast, WYNC, Aug. 31 2020, https://www.wnycstudios.org/podcasts/anxiety/episodes/scared-suburbs. For a more nuanced and in-depth take about the racist and other origins of the suburbs, see Kenneth T. Jackson’s Crabgrass Frontier.

“Florida Whites and the Brown Decision of 1954,” Joseph A. Tomberlin, The Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 51, No. 1, July 1972.

Ibid.

“Race, Education, and Regionalism: The Long and Troubling History of School Desegregation in the Sunshine State,” Winsboro and Bartley, The Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 92, No. 4, Spring 2014.

Ibid.

Lake Highland Preparatory School website, https://www.lhps.org/academics/middle-school, accessed July 1, 2022.

“Equity by Design: What You Need to Know About School Desegregation and Integration and Why it Still Matters,” Sarah Diem, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED624527.pdf

“Segregation in Florida Schools in 2020,” Amy Martinez, Florida Trend, September 25, 2020, https://www.floridatrend.com/article/29950/segregation-in-florida-schools-in-2020.

“Black student disproportionately suspended, expelled in Florida schools,” Leslie Postal, Orlando Sentinel, August 25, 2015, https://www.orlandosentinel.com/news/education/os-black-students-florida-schools-suspensions-post.html.